“I began to associate sex with sin, and I imagine that it had to do with being surrounded in a conservative religion in my home, church, and school. My attitude about sex and sexuality was that it was something that only married or sinful people engaged in.”

– A young Christian woman

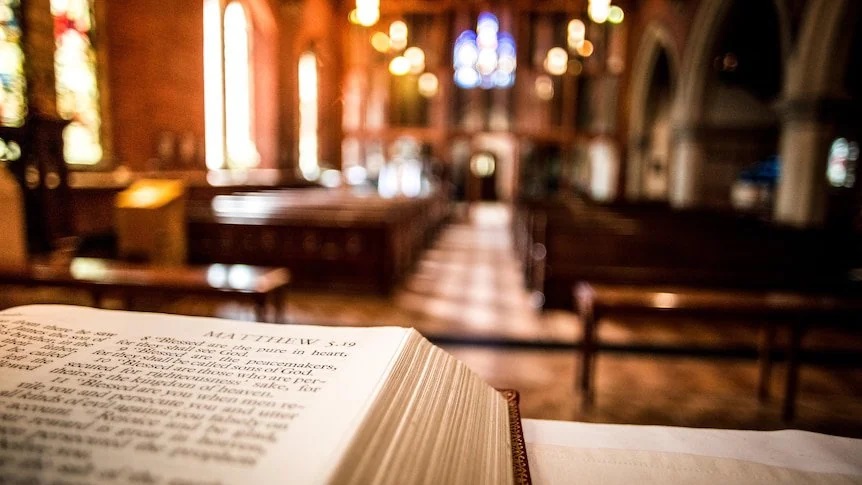

In Sex, God, and the Conservative Church, Tina Schermer Sellers diagnoses conservative Christianity as an incubator of sexual shame and dysfunction. Based in large part on her experience as a therapist treating clients struggling to reconcile their faith and their sexuality, Schermer Sellers explores the church’s “sex negative” ethic, which she attributes to “two millennia of sexual baggage.” (She deems the purity culture “one of the more ascetic and toxic eras in sexual ethics in the last 100 years.”)

A dualism which tore asunder soul and body is largely to blame. This attitude owes more to Greco-Roman culture than the teachings of Jesus. Plato idealized the world of the forms, disparaging the material. Sex was to be transcended through self-discipline. Later philosophers deemed sexual pleasure as inferior to other human pleasures. Stoicism subordinated bodily passion to reason, which was supposed to guide human behavior. As Christianity emerged in this milieu, it absorbed these philosophies, stamping its ethics with a perspective far removed from its semitic Palestinian roots. Early Christian ascetical practices such as fasting and the exaltation of virginity reflected this mindset and were later institutionalized in monasticism. St. Paul was certainly a formative figure in this tradition. Paul’s apocalyptic expectation gave preference to celibacy and colored his view on marriage as a means of fighting temptation (“For it is better to marry than to burn with passion” [1 Cor 7:9]). His ethics focused on the avoidance of porneia, the immorality born out of sexual frustration.

Patristic theology sought to marry Platonist thought with Christian revelation. Origen, Clement of Alexandria, and Pseudo-Dionysius were notable in this regard. But it is Augustine, who Schermer Sellers calls a “sexually troubled soul,” who is most responsible for the spirit/body dualism at the heart of traditional Christian sexual ethics. Before becoming a Christian, Augustine had been a Manichaean, a Gnostic, ascetical sect which sharply divided the spiritual from the material. Peter Brown in Body and Society writes, “For Augustine the Manichaean auditor, sexuality and society were antithetical…. Intercourse, and especially intercourse undertaken to produce children, collaborated with the headlong expansion of the Kingdom of Darkness at the expense of the spiritual purity associated with the Kingdom of Light.” Not only was sexual activity abhorred; even sexual thoughts were verboten. Augustine later renounced and condemned the Manichaeans, but he retained a deep-rooted suspicion of sexuality. Augustine believed sexual “desire was the result of human sinfulness and disobedience to God,” according to Merry Wiesner-Hanks in Christianity and Sexuality in the early Modern World. Augustine’s profound pessimism about human nature was at the heart of his doctrine of original sin. “In his view, no other after Adam and Eve had free will; original sin was transmitted to all humans through semen emitted in sexual acts motivated by desire, and was thus inescapable.” Sexual pleasure itself was a product of concupiscence.

Augustine cast a long shadow. “His legacy of shame, fear of the body, and suspicion of its desires is with us today,” laments Schermer Sellers. Eventually it was institutionalized. The Penitentials, guidebooks for confessors assigning penances, contained, according to Margaret Farley, “detailed prohibitions against adultery, fornication, oral and anal sex, masturbation, and even certain positions for sexual intercourse if they were thought to be departures from the procreative norm.” Gratian’s Decretum, a compilation of canon law, in Farley’s words, “contained regulations based on the persistently held principle that all sexual activity is evil unless it is between husband and wife and for the sake of procreation.” The Reformation, spearheaded by the Augustinian Martin Luther, retained a negative judgement on sexual desire. Descartes’ reduction of knowledge to deductive reasoning and being to cognition can also be seen as a philosophical outgrowth of this attitude.