“But of all pleasures sex is the one which the civilized man pursues with the greatest anxiety.”

Alan Watts

Rummaging recently through a box of old books, I discovered a copy of Alan Watts’ Nature, Man and Woman. Rhonda gave it to me. She was a fan of Watts, who was a former Anglican priest who explored Eastern thought and religion. (He was especially popular among many in the counterculture of the 1960s.) In a chapter entitled “Spirituality and Sexuality,” Watts examines the Christian tradition’s “radically dualistic” split between spirit and nature, which is nowhere more evident than in the realm of sexuality. This dichotomy “abstracts sexuality from the rest of life.” Sexual abstinence is prized because it represents the triumph of the conscious will over nature, which resists control. (Augustine is quoted as attributing “shameful” involuntary arousal to the Fall.) The Church Fathers subsumed all sexual desire into the sin of “demonic” lust. The notion of “holy sex” is almost entirely absent, “save that it must be reserved to a single life partner and consummated for the purpose of procreation.” Abstinence becomes confused with holiness. “The common mistake of the religious celibate has been to suppose that the highest spiritual life absolutely demands the renunciation of sexuality, as if the knowledge of God were an alternative to the knowledge of woman.” The controlling ego, however, only alienates man from himself. “But the sexual act remains the one easy outlet from his predicament, the one brief interval in which he transcends himself and yields consciously to the spontaneity of his organism.” Sex becomes “the great delight.” (I’m reminded of Rhonda’s astute observation that I tend to “intellectualize” my reality, which probably partly explains my attraction to sex as an escape from the conscious will.)

Only in a non-dualistic religious philosophy is sex understood for what it is. The unity which underlies all reality is enacted, almost sacramentally, when the polarities of male and female are bodily united in sexual intercourse. This has profound spiritual implications. Watts writes, “The most intimate of the relationships of the self with another would naturally become one of the chief spheres of spiritual insight and growth.” Rather than a mere escape from the ego, Watts understands the sexual act as a form of self-transcendence in which one enters into communion with the cosmos. This unfolds when one is detached from the established boundaries of the self and the power of the will. “For pleasure is a grace and is not obedient to the commands of the will.” Sexual pleasure has religious significance. Tantric sexual practice is motivated by the belief that it is “a transmutation of the sexual energy which it arouses” so that “sexual love may be transformed into a type of worship.” The ananda (Sanskrit, “ecstasy of bliss”) which accompanies sexual passion is rightly understood as “mystical ecstasy.” Having transcended themselves, what the lovers experience is truly “adoration in its religious sense.” Sex can be a spiritual practice in which the sacred, unitive nature of reality is experienced.

Watts promoted and practiced an “erotic spirituality” (which was the title of one of his works). He elsewhere confessed, “I am an immoderate lover of women and the delights of sexuality.” His religious philosophy reflected his sensuality. “Watts’ main problem with Christianity is that it chafed against his emerging sexual libertinism,” one critic noted. Watts came to believe that sexual activity was “requisite and necessary, as well for the body as for the soul.” Sexual control adheres not in “mere limitations of the frequency of intercourse or the number of his partners” but by exercising “control within the act of sex, and as this will require practice the act cannot be too infrequent (emphasis added).” Sex “culminates in an ecstasy in which there is neither past nor future nor separation between self and other.”

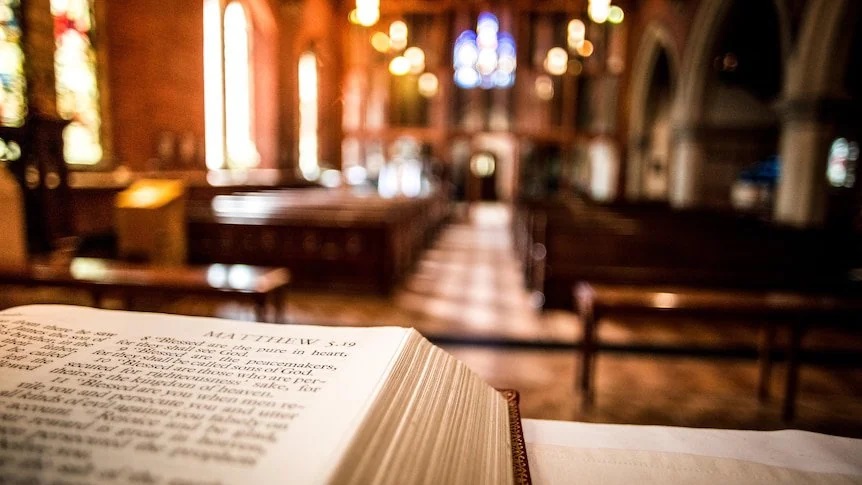

Watts proper Anglican upbringing may explain his sexual infatuation. In Beyond Theology, Watts writes, “For there is a sense in which Christianity is the religion about sex, and in which sex plays a more important role even than in Priapism or Tantric Yoga.” Even today, “the churches function mainly as societies for regulating…sexual mores.” (“Living in sin” does not refer to “ownership of slums or of shares in shady loan companies.”) The glories of sexuality find no representation or expression in ecclesial life. “But what if the Christian poet should have something to say about the revelation of divine glory in the image of a naked girl…? Imagine the screens and niches of St. Peter’s adorned with Baroque equivalents of the tantric sculptures that embellish Hindu temples!” Watts’s suggestion that First Presbyterian Church could offer “the sacrament of ‘prayer through sex'” on Wednesday nights sounds absurd because the church’s reticence on sex precludes even imagining it.

This reticence, Watts continues, reveals that sex “is the principal Christian taboo,” which, in turn, reveals that sex is the “mysterium tremendum, the inner and esoteric core of the religion.” The taboo not only delineates what is prohibited; the taboo contains within it the sacred. The Christian attitude of sex has not truly been disgust but “negative fascination,” for, as Watts archly notes, “those who make much of their distaste for sex lose few opportunities for exercising it.” The taboo attracts as much as it repels. “It is thus that the Church’s intensely negative fascination with sexuality acts as the context and stimulus for a prolific erotic life.” It provokes “those who resist temptation to the point where they are at last compelled to give in.” This is not mere hypocrisy, but “sexual ambivalence” which stimulates both lust and guilt. It explains the “double life” of the prelate who “really believes in all that he preaches, but finds that it is overwhelmingly impossible to practice because the legs of one of his secretaries” proves irresistible.

“The religions of the world either worship sex or repress it; both attitudes proclaim its centrality,” Watts writes. For Christianity, “the resolution of the problem must be the divinization of sexuality.” Beneath the veil of the church’s prudishness we glimpse what it strains to conceal: that sexual intercourse is “a direct way of realizing the mystical union.” Freud interpreted religion as a sublimation of the libido. But what if the sexual impulse is the religious impulse? This has theological implications, for “it should follow that human generation has its archetypal pattern in the divine act of creation. The Hindus portray this quite openly in images of Shiva or Krishna with his śakti or feminine aspect, embracing him with her legs around his loins.” In the end, sex should evoke “cosmic wonder.”

In Nature, Man and Woman Watts writes:

“Without–in its true sense–the lustiness of sex, religion is joyless and abstract.”

The lustiness of sex. This stuck with me because Rhonda was a lusty gal. A shelf full of books on sacred sexuality on her bookcase testified to her interest in the intersection of spirituality and sexuality. “For the spiritual practitioner, sexual intercourse is an opportunity to encounter the sacred dimension,” Georg Feuerstein writes in Sacred Sexuality: The Erotic Spirit in the World’s Great Religions. (Rhonda gave me a copy of that book, as well.) Sacred sex is “about communing or identifying with the ultimate Reality, the Divine.” Yet sacred sex can be cast in such an ethereal light that the carnal, bestial impulses that drive most sexual activity can be obscured. The lustiness of sex. When we were frantically fucking in the back of Rhonda’s car after class, “the sacred dimension” of what we were doing wasn’t exactly at the forefront of my mind.